Early. Not Broken.

[Guest blog] Seasoned investor Ido Sum offers a data-driven alternative take on where we might be, hoping to ignite a discussion...

First, I want to thank Maxime and Max for this opportunity. As an avid user of their data sets over the years, seeing their scale and growth couldn’t make me happier, so I was grateful to be invited to ‘brainstorm’ on this platform. Second, adding the quick disclaimer that after recently parting ways with TLcom, the views below are mine and mine alone, and do not represent anyone else’s. So now - let me dive right in…

After a decade of watching Africa’s tech ecosystem grow from almost nothing into something very real, it’s tempting to judge it against “US VC 2025” – big growth funds, frequent $1b+ exits, IPO headlines and secondary markets, and conclude we have a not-so-flattering outcome. But if you zoom out and look at the data, Africa today looks much closer to the US in the 1970s–80s, Israel in the 1990s, Europe in the early 2000s and India in the early 2000s than to today’s fully-baked playbooks. In all of those markets, the first 15–25 years were dominated by small funds ($10m–$50m), modest rounds, exits mostly in the $25m–$300m range, very few unicorns and a long, slow process of building trust with capital providers. In other words: what we are seeing in Africa is not “broken” – it is what “early” has always looked like.

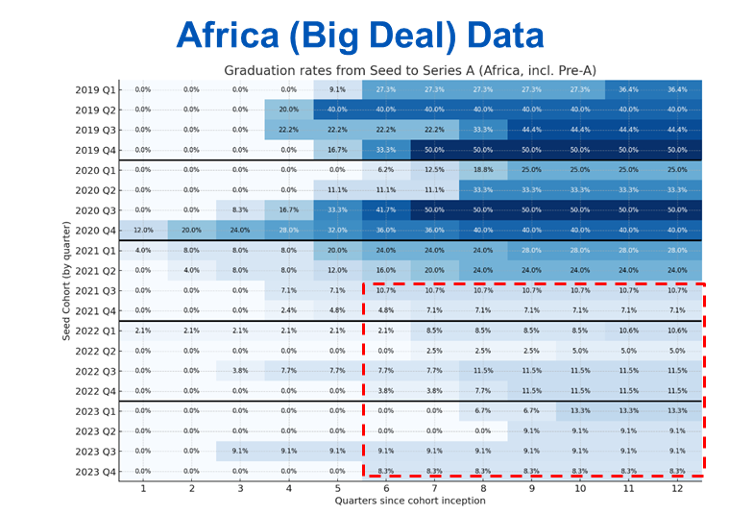

One useful way to see this is through the ‘conversion funnel’. In the US, CB Insights tracked ~1,100 tech companies that raised seed between 2008–2010: roughly half went on to Series A, around a third to Series B, about 30% had some kind of exit within ~10 years, ~10% exited for more than $50m, and about 1% became unicorns. More recent data from Carta and others still puts Seed→A graduation in the ~30–40% band in mature markets. Now compare that with Africa using Africa: The Big Deal’s dataset: Between 2019–2022, 582 African startups raised Pre-Seed or Seed. Of those, just ~26% raised any subsequent round, 16% reached something like Series A (incl. Pre-A), 4.5% made it to Series B, only 0.5% reached Series C+, and 2.9% exited. If you blend in another ~500 companies that first appear at Venture/A/B/C (no recorded seed), you get the same ~1,100 startups entering the equity funnel over those four years, with only ~21% making it to Series A, ~5% to Series B and <2% to Series C+. The message is simple: it’s not that African founders are weaker, it’s that growth-stage capital is thin and the funnel past A tightens very quickly.

The exit picture tells a similar story. Looking at larger African tech exits (>$50m) from roughly 2015–2025, you get just over 20 deals with total disclosed value around $5b. The “average” company in that group raised roughly $250m (equity + debt) before exit (those above $100m exit value skew higher in capital raised, those in the $50m–$100m band closer to ~$75m). Time to exit sits at about 10.5 years. Nearly half of those exits are South African, with Nigeria and Egypt following and a scattering from Kenya, Morocco, Tunisia, Senegal and Ghana – which maps neatly to where corporate balance sheets and M&A infrastructure are deeper. Roughly three-quarters of these exits are strategic M&A. IPOs are still rare (one US, one Egypt, one SPAC-type), and most outcomes sit in the $50m–$150m range, with a few better-known outliers like Paystack, DPO and InstaDeep. Again, if you compare this to Israel, India or Europe in their second decade, it looks surprisingly normal: early ecosystems are dominated by small and mid-sized domestic or regional M&A before the big, repeatable $500m–$5b outcomes show up.

So what do we do with that? Realism is not pessimism. It can be optimism, with a sense of reality intact. If the median “good” outcome for the next 10–15 years in Africa is more likely to be a $50m–$250m trade sale than a $5b IPO, then our fund sizes, strategies and expectations should reflect that. Smaller, focused funds ($20m–$75m) can still generate excellent returns if they’re moved by $100m–$200m exits and underwrite to realistic buyer universes: local banks and telcos upgrading infrastructure; regional consolidators; global strategics who care about licences, distribution or infrastructure in Africa. At the same time, we need to accept that in the absence of the non-equity scaffolding other ecosystems had (R&D grants, guarantees, working capital instruments, venture debt at scale), equity alone is carrying too much weight, and that makes the funnel even harsher. None of this is a reason to be pessimistic. It is a reason to treat Africa as “early, not broken”, and to design capital, exits and expectations accordingly.

If you want to comment, challenge, push back or just join the discussion, please do so here. And for those who want to go much deeper into the data, the global comparisons and the implications for fund strategy, the full essay is here: